How do you drive in China? In 2001, when Peter Hessler applied for a Chinese driver’s license, he entered a brave new world. In Beijing alone, almost a thousand drivers registered on average each day, the pioneers of a nationwide auto boom. Most of them came from the growing middle class, for whom a car represented mobility, prosperity, modernity. For Hessler, it meant adventure. The questions of the written driver’s exam suggested a world where nothing could be taken for granted:

223. If you come to a road that has been flooded, you should

a) accelerate, so the motor doesn’t flood.

b) stop, examine the water to make sure it’s shallow, and drive across slowly.

c) find a pedestrian and make him cross ahead of you.282. When approaching a railroad crossing, you should

a) accelerate and cross.

b) accelerate only if you see a train approaching.

c) slow down and make sure it’s safe before crossing.352. If another motorist stops you to ask directions, you should

a) not tell him.

b) reply patiently and accurately.

c) tell him the wrong way.

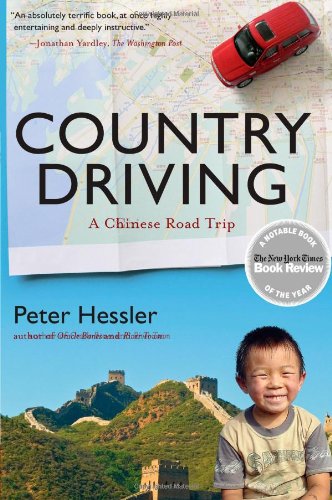

With license in hand, Hessler spent the next six years researching the final book in his China trilogy. He began the series with River Town, which explored the theme of geography in a fast-changing country, and then, with Oracle Bones, he examined the role of history in today’s modern society. In Country Driving, he turns his attention to development, capturing the human side of China’s economic transformation.

Through three distinct stories, Country Driving tracks the rise of the automobile in Chinese life. The book begins with “The Wall,” an account of a months-long road trip that follows stretches of the Great Wall. All told, Hessler drives 7,436 miles across northern China, the once-great cultural heartland that nowadays is rapidly losing its population to massive urban migration. Picking up hitchhikers, talking to locals, and visiting relics of the past, Hessler creates a vivid portrait of this changing region.

In “The Village,” he narrows his scope to a single settlement in the midst of transition. North of Beijing, Hessler rents a farmhouse in a small, remote village called Sancha. When Hessler first begins visiting Sancha, the place is accessible only by a dead-end dirt road, and it’s rare to see outsiders. But soon the government undertakes a major road-building campaign across rural China, and the route to Sancha, like so many others, is paved. Suddenly the village is accessible, and meanwhile the capital’s auto boom is creating a new class of citizens eager to explore the countryside. In Sancha, a family called Wei tries to respond to these developments, shifting from farming to business. Over the span of six years, Hessler observes in detail the effects of this change, which range from shifts in diet and health, to a growing interest in religion, to new tensions within the local branch of the Communist Party.

In “The Village,” he narrows his scope to a single settlement in the midst of transition. North of Beijing, Hessler rents a farmhouse in a small, remote village called Sancha. When Hessler first begins visiting Sancha, the place is accessible only by a dead-end dirt road, and it’s rare to see outsiders. But soon the government undertakes a major road-building campaign across rural China, and the route to Sancha, like so many others, is paved. Suddenly the village is accessible, and meanwhile the capital’s auto boom is creating a new class of citizens eager to explore the countryside. In Sancha, a family called Wei tries to respond to these developments, shifting from farming to business. Over the span of six years, Hessler observes in detail the effects of this change, which range from shifts in diet and health, to a growing interest in religion, to new tensions within the local branch of the Communist Party.

In “The Factory,” the third part of Country Driving, Hessler turns his attention to urban China. He spends three years researching in Lishui, a small southeastern city where officials hope that a new government-built expressway will transform a farm region into a major industrial center. The city’s story is told through the experiences of one factory, which produces an obscure product: the nylon-coated metal rings that attach to bra straps. For the typical American consumer, such an object doesn’t deserve a moment’s thought, but in China such it encompasses a world of determination and desire. Fortunes have been made and lost, industrial espionage has been committed, even death threats have been issued — all in the service of producing this tiny, forgettable object.

Like so much of Hessler’s work, “The Factory” focuses on average people, telling the story of Lishui’s boom through the experiences of small-time entrepreneurs, migrant workers, and self-educated technicians. And Country Driving tracks the movement of the nation as a whole. Having started in the countryside, with the stately image of the Great Wall, the book proceeds to new cities where migrants are engaged in producing objects like the bra ring — artifacts of the future. Along the way, Country Driving illuminates the vast, shifting landscape of a traditionally rural nation that, having once built walls against outsiders, is now constructing factory towns to make goods for the world.

Like so much of Hessler’s work, “The Factory” focuses on average people, telling the story of Lishui’s boom through the experiences of small-time entrepreneurs, migrant workers, and self-educated technicians. And Country Driving tracks the movement of the nation as a whole. Having started in the countryside, with the stately image of the Great Wall, the book proceeds to new cities where migrants are engaged in producing objects like the bra ring — artifacts of the future. Along the way, Country Driving illuminates the vast, shifting landscape of a traditionally rural nation that, having once built walls against outsiders, is now constructing factory towns to make goods for the world.

For forty miles I followed a small road into the Gobi… I was off the map now, in unmarked territory; the City Special bounced over low rocky hills. After ten miles the track terminated at the ruins of Hecangcheng. It’s an ancient fortified granary, built over two thousand years ago to serve the Han dynasty soldiers who were stationed here. In this part of the desert, on the western edge of the empire, the Chinese had constructed forts instead of a wall. The land is so flat and barren that I could see the next one in the distance, three miles away. I had reached the end of the line – the stream of continuous walls had given way to scattered forts, like final drops from a spigot that had been shut off.

There was nobody else at Hecangcheng. The government planned to build a paved road to the site, but the modern construction had yet to begin and the place remained isolated… I pitched my tent in the shadow of the fort. A small stream ran in the distance, surrounded by marshland, like a thin ribbon of green tied taut across this parched landscape. The sky was restless — fugitive clouds scattering across a dome of blue. At midnight the gusting wind shook me awake. It hummed across the Gobi, and whistled through the ruins, and I lay there listening to the same song that stirred soldiers in the days of the Han.

— from “The Wall,” pages 120 – 121